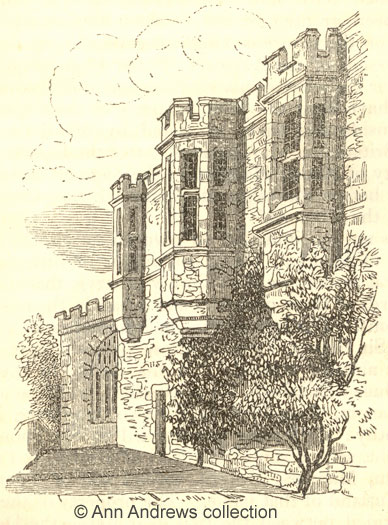

Haddon Hall.

G. Rowe. Lith

The lithograph of Haddon Hall was published in

William Adam's "The Gem of the Peak" in 1840[1].

Adam also wrote the following:

"On Haddon's Bank as the fisherman strays,

When the clear cold eve's declining,

He sees the Towers of other days

In the WYE beneath him shining."

Chapter VI. Approach to Haddon - Preliminary Remarks.

"THE sun was fast declining in the "far west" when

we attained the eminence near Haddon. This relic of a bygone

age, with its weather-beaten towers and battlements, we observed

peering from amidst the thick foliage; its numerous turrets

and windows gleaming in the sunlight; and being in part strongly

shaded by its umbrageous envelope, it presented a fine object

for the pencil. The situation of Haddon is pre-eminently beautiful.

It stands on a shelving, and rather elevated, mass of the first

limestone, overlooking the entire dale and its meandering and

lovely Wye, backed by extensive woods and surrounded by majestic

trees. At first sight it has more the appearance of an old

fortress than what it really is, a Hall chiefly in the Elizabethan

style, and without any effectual defences, as we shall presently

see from the following remarks, which we beg to make

while we contemplate this interesting structure ; - a structure

which assisted the imagination of Mrs. Radcliffe in its wildest

flights, when writing the Mysteries of Udolpho[2].

Haddon is decidedly one of the finest specimens of a Hall

of the olden time in existence. The old tower, with narrow

loop-holes and gloomy uncomfortable rooms, is the only part

which retains that stern character, the peculiar

feature of that iron age when "every man's hand was against

his fellow;" that age of darkness and military despotism

which succeeded the destruction of the Roman power by the savages

of the north. In these times, each successful conqueror parcelled

out the nation or territory subdued, into so many military "fiefs," held

only by virtue of devotion to their Prince, who claimed their

services whenever circumstances required. These were again

subdivided into smaller portions, to their dependants and retainers,

who held their lands upon precisely the same tenure of doing

fealty to their lord, and could be called upon at any moment

to defend his person and domains from the aggression of a neighbour,

or to proceed with him to serve their common chief, either

at home or abroad. Europe thus became universally subject to

military rule, which gradually softened, and settled down into

what is termed the feudal system; a simple modification of

this military despotism, with a somewhat less stern aspect,

still retaining too much of its form and sanguinary

character.* The bulk of the population, under this system,

were no better than serfs of the soil, perfectly at the will

of their masters, and plunged in the grossest ignorance and

superstition. Surely it may be emphatically said of this period,

that " darkness covered the earth, and gross

darkness the people." This was a time of peril, when

caprice, passion, ambition, or avarice, was the order of the

day, and when either happened to be in the ascendant, pretexts

were not long wanting to make an attack upon a neighbour to

gratify a bloodthirsty desire, or accomplish any purpose of

conquest or revenge, as the case might be. Can we wonder, therefore,

that everywhere sprung up those gloomy, wretched abodes, those

castles and fortresses which frown upon

a country, surrounded by moats and defended with bastions,

draw-bridges, and towers of immense strength. The times required

it. No man felt

safe a moment from the inroad of the foe. The old part of Haddon,

which has elicited these remarks, is a specimen of the architecture

of those times, and it is said to be older than the conquest;

but this forms only a small part of (shall we say) modern Haddon.

The first great quadrangle, and the three sides of the second,

are built in the style of our ancient Halls - "a composite" -

a combination of the Gothic and Saxon, without those powerful

and gloomy defences, which were not so necessary in more recent

times, when men became united, and subject to law, and one

common form of government.

Haddon, therefore, as a quiet country seat of our gentry

in the sixteenth century, kept still in good repair, with all

its ANCIENT honours about it, just as deserted by the family

a hundred and seventy years ago; and really retaining all that

character, as if they had quitted it but yesterday, is a beautiful

specimen of that age."

Footnotes:

* The small Baronies and Baronial Courts and Manors are still

existing relics, of these times, only shorn of their power".

"We give a sketch here, by [Samuel] Rayner, of the three

beautiful Oriels

in the Earl's State dressing and bed-room" (Adam) [1].

Henry Duesbury traced the history of Haddon Hall's development, dividing it into five distinct periods.

In 1851 Duesbury, a distinguished architect of the day[3],

traced the history of Haddon having consulted documents exhibited by the Archaeological Association at Derby,

with permission from the then Duke of Rutland. In 1837 he had written a supplement to Samuel Rayner's

1836 book on Haddon Hall[4]. The list of the building's development,

below, has been compiled from information provided in T. S. Hall's guide 1873 book[5]:

- Approximately 1070-1250.

The chapel's south aisle, some of its walls, the north east tower and portions of the walls in

the south front.

- About 1300-1380.

The great hall and offices, the hall-porch, the lower west window of the chapel, repairs to and

rebuilding of the north east tower, some other work in upper court under the long gallery.

- 1380-1470.

Eastern portion of the chapel, rebuilding the upper portion of its west end and repairs to the

same and buildings on the west side of the upper court.

- 1470-about 1550.

Fitting and finishing the dining room, the western range of buildings, and the western end of

the north range.

- 1550-1624 and onwards.

Offices, alterations of east buildings in upper court, the long gallery and gardens and terrace,

the pulpit and desk and pews in the chapel, the barn and bowling green.

|

References (coloured links are to transcripts and

information elsewhere on this web site):

[1] Adam, William (1840) "The Gem of the Peak", London;

Longman & Co., Paternoster Row - see onsite

transcript.

[2] Radcliffe, Ann Ward (1794) "The Mysteries of Udolpho",

London: Longman, Hurst, Rees & Orme. Jane Austen mentioned the book in "Northanger Abbey".

[3] Duesbury, Henry (1851) "Haddon Hall" from the

"Journal of the British Archaeological Association", First Series, Volume 7, Issue 3.

[4] Rayner S[amuel] (1836) "The History and Antiquities of Haddon

Hall", published by Moseley, Derby.

[5] Hall, Spencer Timothy (1863) "Days in Derbyshire ..." With

sixty illustrations by J. Gresley (artist), Dalziel Brothers (illustrators). Simpkin, Marshall and Co,

Stationers' Hall Court, London, and printed by Richard Keene, All Saints, Derby.

|