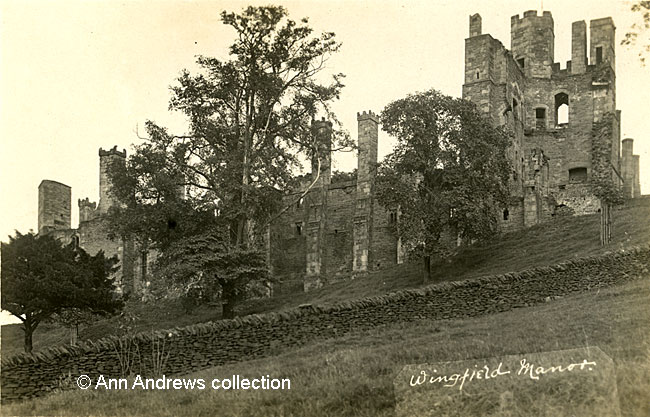

"Neither the picturesque nor the strictly architectural traveller should miss Wingfield Manor House. Its tall ruins

... are an extremely dramatic sight".[1]

Wingfield Manor was begun about 1440 by Ralph, Lord Cromwell who was Treasurer of the Exchequer in the reign

of Henry VI[2]. Whilst the Cromwell family had possessed the manor

of West Hallam from an early period, until Ralph inherited the manor of South Wingfield the family do not

seem to have had a residence in Derbyshire. Lysons tells us that he acquired the manor "by compromise, after

a long lawsuit with Sir Henry Pierrepont", as he was the nearest kin to Margaret Swillington. He also owned

Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire, which he renovated. Cromwell "died without issue, though had, before his

death, sold the reversion of the manor of Winfield (as it was then called) to John Talbot, second Earl of

Shrewsbury[3].

Cromwell's manor was "surrounded by a park of one thousand acres" and "an extensive lake, at

the head of which was a mill, spread over the valley on the north and west[4]."

His manor wasn't the first building on the site, though. This did not come to light until an archaeological survey

was undertaken of a bank and ditch some years ago, which discovered earlier medieval occupation[5].

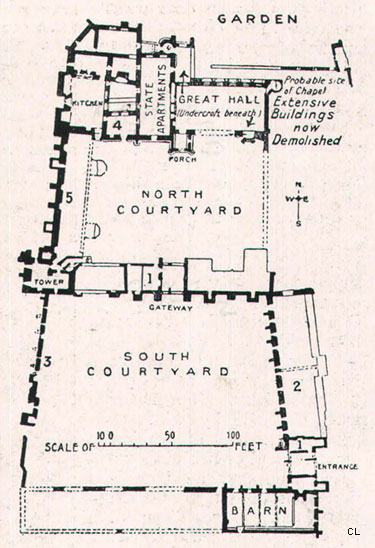

|

|

1909 map, from Country Life[6].

Today's entrance to the Manor is not shown. |

John Talbot completed the building and Wingfield remained as one of the principal seats of his successors until 1616.

The 4th earl, George, died at Winfield on 26 July 1541; he was buried at Sheffield. The fifth Earl, Francis, was made

Privy Council to Edward VI and was one of the chief mourners at his funeral. He then declared allegiance to Lady Jane

Grey, writing to Queen Mary to deny her the crown. Yet he was immediately pardoned when she came to the throne! He

became Privy Council to Elizabeth. George was his only surviving son and became the sixth Earl. Gilbert Talbot,

the seventh Earl, died without a male heir as his two sons, John and George, had died as infants[7b].

The co-heiresses of Gilbert Talbot - and their husbands - inherited Winfield Manor[8].

The Manor was built on a hill, with the ground on three sides sloping steeply. There was also a dry moat and a wall at the northern

end, where gardens were laid out. It would have had extensive views, especially from the High Tower.

Original entrance (no. 1 on the above map), from inside the Manor's grounds. The Barn is on the right.

Lord Cromwell, the Shrewsburys and Mary Queen of Scots would all have entered the Manor through this gate.

The roof, battlements, side turrets and parts of the upper stage no longer exist [4].

When Rev. Errington of Ashbourne visited in the mid-nineteenth century he mentioned that the steep carriage approach "... brings you

at length to the gatehouse, which has a central and a side archway, the latter being for foot passengers only, and abutting onto the porter's

lodge. This gatehouse is about sixteen feet through, having corresponding arches on the western face. A large lateral arch opens from the footway,

to enable the gatekeeper, stepping across, to communicate with the horse and carriage passage; this arch is semi-circular, the others being obtuse,

except the main eastern one, which from the dropping of the key-stone, and from repair has now a semi-circular appearance. ... Like the rest of the

structure, it is built of fine hard stone, which exhibits few marks of corrosion[4]"

The entrance gateway opened onto a large square outer court or quadrangle where the less important members of the household lived. The inner

court was more stately. The great banqueting hall was 72 ft. by 36 ft., underneath which was a spacious crypt[9],

which has four entrances.

The Crypt or Undercroft, one of the finest in England, was built in two wide aisles with a vaulted

and groined roof. There are many carved details on both the capitals of columns

and on the large traceried bosses on the vaulting ribs, an example of which can be seen above. Taken about 1900.

Mary Queen of Scots was the first cousin once removed of Elizabeth I and her siblings; her grandmother, Margaret, was

Henry VIII's older sister. When she fled from Scotland she was hoping for Elizabeth's protection, not for incarceration.

By the time of her imprisonment Edward VI and Mary I had both died, so Mary had become the heir to the English throne; she

was also nine years younger than Elizabeth and Elizabeth would not marry.

She was first at Wingfield on 2 February 1569 and returned for a six month stay in April of the same

year[10]. Elizabeth had placed her in the custody of George Talbot, sixth Earl

of Shrewsbury who was the fourth husband of Bess of Hardwick, in January 1568 and she remained in his care until

September 1584. It was said the her "misfortunes began in her cradle, and accompanied her, with little intermission,

to her grave"[9]. Alison Plowden described her as "very

feminine", whereas Bess of Hardwick was shrewd and successful. They were both skilled needlewomen, which

was fortunate for the length of time they spent together, but "both possessed devious scheming brains"[11].

The historian Thomas Blore commented on Earl George's attitude to the Queen of Scots whilst in his custody

: "In this service he preserved his fidelity to Elizabeth unshaken : but he was so perpetually seized by

her suspicions, and those of her ministers" that it "appears to have inflicted upon him a severity of

punishment little inferior to that of his unfortunate captive". So sometimes his behaviour towards Mary made

her resent him, whilst if he showed her any kindness his wife became jealous[7b].

Inner or North Court, with the High Tower on the left and porch to the State Apartments on the right, 1892.

Mary's "suite of apartments ... was on the west side of the north court", next to the tower. It was remembered

as "the most beautiful part of the building: it communicated with the great tower". Mary was reputed to have

seen her friends, with whom she communicated, approaching from this vantage point[7b]. Mary

became very ill in 1869, when she had only been back at Wingfield for three weeks, and had to be taken elsewhere

whilst her apartments were thoroughly cleansed[12].

She was heavily guarded. "It appears from Sir Ralph Sadler's papers published in 1809[13],

that there were two hundred and ten gentlemen, yeomen, officers and soldiers, employed in the custody of the

Queen of Scots at Wingfield in the month of November, 1554" when she was once more in residence[9].

Her personal household consisted of five gentlemen, fourteen servitors (attendants/servants), three cooks,

four boys, three gentlemen's men, six gentlewomen, two wives, and ten wenches and children[14].

On 25th January 1585 Mary was removed from Wingfield Manor and taken to Tutbury Castle[9].

The Babington Plot, in which local landowner Anthony Babington of Dethick was heavily involved, was to have disastrous

consequences for both Mary and its ringleaders[15].

After her execution at Fotheringhay Castle she was taken to Peterborough Cathedral for burial. However, in 1612 her

remains were transferred to Westminster Abbey on the orders of her son and reburied there in a magnificent marble tomb.

Oriel Window, North Court.

"It has been a very beautiful edifice ... from the remains on the north side of the principal court:

these consist of a porch and a bow with three Gothic windows". The window arches are pointed and

both porch and bow window are embattled. Just below the battlements is a fascia of quatrefoils and roses [9].

On one of the battlements are Cromwell's arms.

One of Imanuel Halton's sundials can be seen above the window on the right (see photos on the next page).

Cromwell's arms.

Arg, a chief over G, over all a bend, Azure [3].

Small fireplace, with chimney breast, and stone stairs near the kitchen.

With so many people in the household when the family, their servants, their prisoner, her retinue and many

guards were in residence the necessary catering would have been on a vast scale. The manor's kitchen was next

to the royal apartments. It contained three very large fireplaces, one of which is shown below. Mary was said

to have consumed, or at least been offered, about sixteen dishes at both courses[7b]

and some of her staff dined before the queen, for obvious reasons. But with so many mouths to feed whilst Mary was in residence,

it is quite possible that another kitchen was housed elsewhere in the Manor, but was later destroyed. Unfortunately, there is

absolutely no evidence for this.

One of the very large fireplaces in the kitchen.

A hearth is in one corner, perhaps where a large cauldron for boiling water was kept.

There would also have been spits for roasting meats and game.

Two very similar wide fireplaces are also in the kitchen, on either side of a corner.

There is a picture of a mediaeval hearth at Dethick's Manor Farm,

though it was clearly on a smaller scale than what was required at Winfield Manor.

|

|

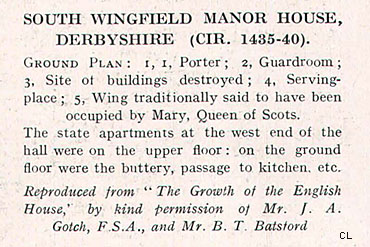

There were also two bread ovens inside one of the kitchen's big fireplaces.

This is the smaller of the two. A fire would have been lit to heat it up, and when it was hot enough the

embers would have been removed and the bread put in to cook. The second, larger, bread oven on the right

of this one is not shown. |

The apartments where Mary Queen of Scots lived in no longer exist (no.5 on the map above). They may have been destroyed by Sir

John Gell or the stone could have been removed by the Haltons (see next page).

However, the chimneys and or garderobe turrets (the large square projections) seen on the final image (at the bottom of the page) remain.

They seem to have served a dual purpose as every room on the upper floor contained a fireplace and latrine, grouped together.

There is also evidence of a "loo" in the tower's ground floor, flushed from above.

Hidden below the floor.

We can see floor supports in the wall, beneath which is an arch and the sloping bottom of a garderobe.

It was designed to deflect the human waste, as it fell, away from the manor's walls.

The arched "recesses" at the bottom of the wall were probably entrances to culverts, so the liquid waste would

drain away. Where it came out of the walls can still be seen today. The remainder would have been dug out and removed

by a hapless servant.

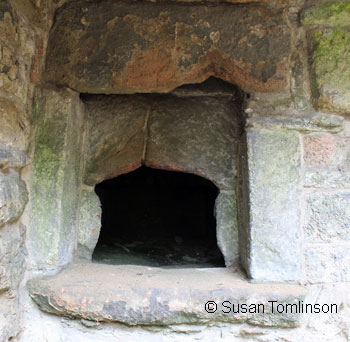

The 1920s, or thereabouts.

External view of the tower and west wing, with many chimneys and garderobes.

Although the top image seems to show an almost complete tower, this view reveals that its outer wall has largely gone, probably damaged after the siege of 1646.

The kitchen was close to the further end of manor. We can see the protruding wider wall of the square chimney, but much is hidden behind the tree on the left.

There is more about Wingfield Manor on the next page. There is more about Wingfield Manor on the next page.

|